Beyond the Headlines

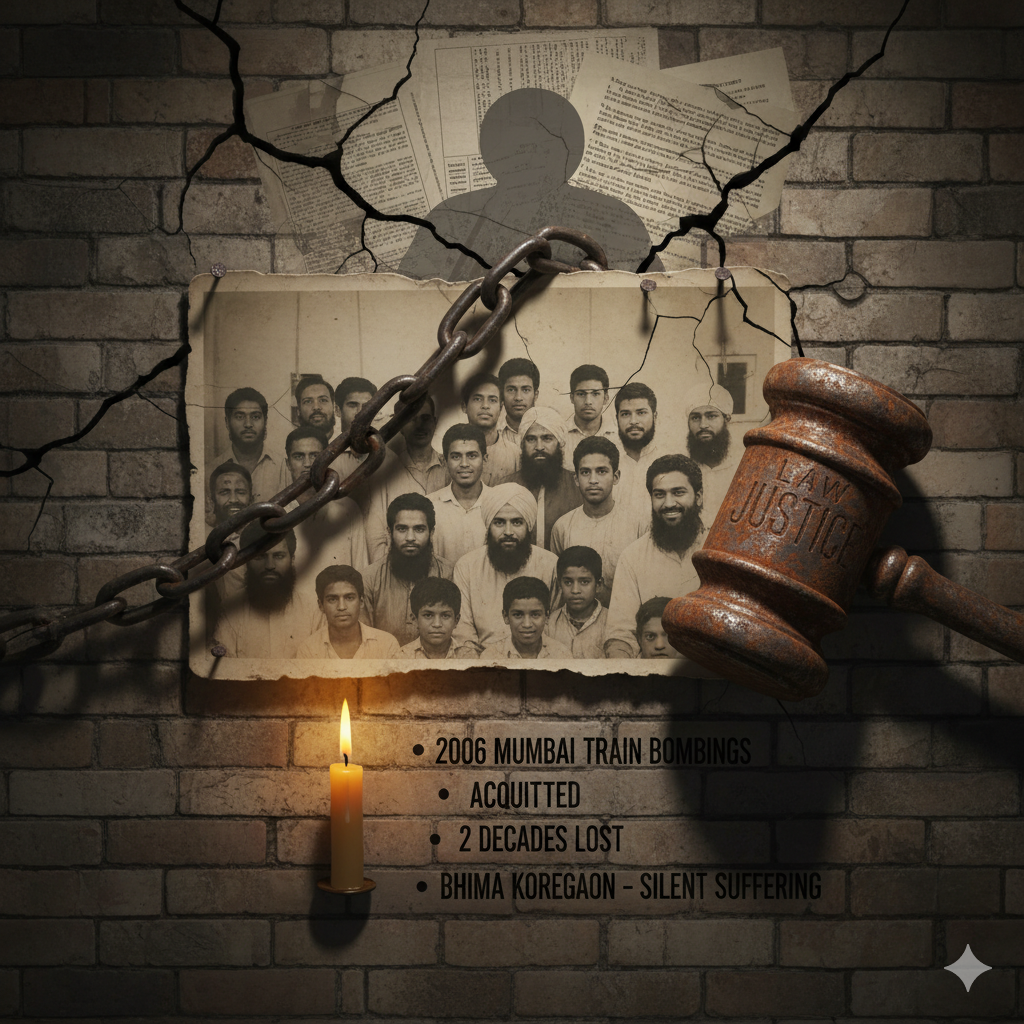

When the Bombay High Court acquitted 12 men convicted in the 2006 Mumbai train bombings calling the Anti-Terrorism Squad’s investigation an “utter failure” it posed a truth: the prosecution had “utterly failed to prove the case against the accused,” and “it is hard to believe that the accused committed the crime.” But can a court undo two decades of shattered lives, suspended dreams, and injustice?

Talal Asad, in On Suicide Bombing, sharpens our moral lens: “Violence is embedded in sovereignty, including democratic ones…We often fail to recognize the violence that sustains everyday normality.” He reminds us that spectacular violence bombings, riots, terror is dramatic because it ruptures everyday life. The quieter violences decisional, institutional, mundane are foundational. Those “invisible” violences, he writes, “manufacture conditions” that make the spectacular possible.

In India, this dynamic repeats across cases. Consider Bhima Koregaon, where intellectuals and activists, including Prof. Hany Babu a Malayali and former Delhi University professor remain imprisoned without conviction. Their detentions are not sensational: no explosions, no headlines. Yet they represent a form of secular violence embedded in statecraft: incarceration without closure.

These cases reveal how secular ethics operate under majoritarianism. In Formations of the Secular, Asad critiques the idea of state neutrality: it is “deeply structured by dominant identities,” enabling legal brutality as long as it remains faceless. In the Mumbai blasts case, we see this in action: Muslim men convicted on shaky witness testimony, coerced confessions, questionable forensics all later declared unreliable by the court. The flames of suspicion linger long after exoneration.

How many lives like these remain uncounted?

Growing up, I believed violence meant sudden rupture: explosions, riots. But I was blind to latent violence: the normalized exclusions, biased policing, injustice, and suspended lives. This daily violence “kills, mutes, annihilates desires, aspirations, and futures of many perishable, marginalized lives,” as I once realized. It doesn’t shock. Yet it sustains the equilibrium that dramatic violence disrupts.

In the Bombay case, the High Court’s verdict exposed not only investigative failings but structural violence: from forced confessions to prolonged incarceration. The ATS became judge, jury, and gaoler. Asad would argue this is the secular state manufacturing violence under law’s camouflage. The Bhima Koregaon detainees, including a Malayali scholar, live this structural violence. Their silent suffering underscores how secular institutions, infused with majoritarian norms, normalise indefinite detention, stigmatization, and intellectual suppression. The state’s capacity for violence through laws, surveillance, ill‐supported claims sizes up beyond the limited scale of terrorist acts.

What Kerala or India needs is not only outrage at spectacular violence but sustained attention to everyday violence. This means legal advocacy, public scrutiny, and activism around cases like Koregaon not only when headlines flare, but when verdicts linger in the balance. Only then can we dismantle structures that criminalize dissent and normalize oppression. Only then might we ask: who returns lost years? Who restores dignity? Who rebuilds futures? Perhaps finally our secularism will be more than a constitutional abstraction it will be a moral guard against all forms of violence: dramatic and insidious, spectacular and silent.