Sword and Scripture ; Ethics in Islamic Warfare

Islamic jurisprudence, for centuries, has meticulously articulated principles governing armed conflict that emphasize humanitarian consider ations, proportionality, and moral restraint. This sophisticated and often misunderstood framework offers valuable insights into the ethical parameters of warfare.

THE FACT THAT CONFLICT has existed throughout human history demands a thorough and continuous investigation into the moral standards that ought to guide war. The Islamic ethics of war offer a frame work of extraordinary complexity, depth, and regrettably, frequent misunderstanding within this crucial global discourse. Over the course of more than fourteen centuries, Islamic jurisprudence has painstakingly articulated a comprehensive set of principles governing armed conflict, far from endorsing unchecked aggression, indiscriminate violence, or a rejection of humanitarian norms.

Even in the face of the harshest and most difficult realities of war, these principles demand profound moral restraint, strictly enforce proportionality in the use of force, and rigorously prioritize humani tarian considerations. This lengthy article aims to explore the complex web of these ethics, tracing their rich historical development through centu ries of classical and modern Islamic scholarship, critically analyzing their enduring and profound relevance in navigating the complex challenges of modern warfare, international law, and the pursuit of world peace, and thoroughly exploring their foundational sources in divine revelation and the exemplary prophetic tradition. The Quran, the Sunnah, and scholarly interpretation are the fundamen tal pillars.

The core of Islamic war ethics is a dynamic, intricate, and rich interaction between its two main authoritative sources: the Sunnah, which is the entire collection of customs, sayings, and unspoken blessings of the Proph et Muhammad and serves as a useful guide for Muslim living, and the Quran, which Muslims consider to be the literal, unadulterated word of God revealed to Proph et Muhammad. The entire comprehensive structure of “just war” (often referred to as jihad qital or defensive struggle) principles within Islamic tradition has been painstakingly constructed and refined upon the centu ries-long interpretation, rigorous exegesis, and extensive elaboration of these foundational texts by generations of distinguished Islamic scholars.

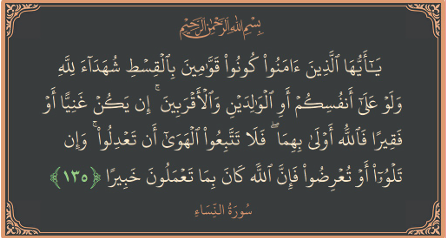

The Quran constantly frames warfare within extremely strict moral, legal, and ethical boundaries, even though it openly acknowledges the sad and frequently tragic reality of armed conflict as an occasional, albeit regret table, necessity in human affairs. Emphasizing with divine clarity that fighting is only acceptable as a last resort, strictly in self-defense, or to repel manifest and ongoing aggression against one’s community, land, or the oppressed, it strongly and unequivocally rejects unpro voked aggression.

This basic defensive mindset is emphasized time and again in key verses, such as “Fight in the way of Allah those who fight you but do not transgress. Indeed. Allah does not like transgressors” (Quran 2:190). This strong and unwavering prohibition against transgression (la ta’tadu), which includes going beyond bounds, acting unfairly, or using excessive violence, is not just a moral precept; it is a fundamental legal principle. It clearly states that the use of excessive force, disproportionate retaliation, or the deliberate targeting of non-combat ants is strictly forbidden by God, even in cases of legal defensive warfare. In addition, the Quran emphasizes time and again how crucial it is to pursue peace, recon ciliation, and an end to violence whenever enemies show a sincere desire for it: “And if they incline to peace, then incline to it also and rely upon Allah. Indeed, it is He who is the Hearing, the Knowing” (Quran 8:61). Islam strongly favors diplomatic solutions, negotiation, and the end of hostilities at the earliest feasible and morally acceptable opportunity. This explicit, straightforward, and unambiguous divine directive demonstrates a basic and deeply rooted preference for peace over conflict. T he spirit of these verses urges not only reactive but also proactive steps toward peace.

The Sunnah provides invaluable practical guidance and a well-documented standard of conduct during times of war because it is the living embodiment and practical exposition of Quranic principles through the example of Prophet Muhammad’s life and deeds. His instructions to his commanders and armies prior to sending them into combat serve as a powerful example of the humanitarian values he ingrained. According to several Hadith collec tions, which were notably expanded upon by classical jurists like Al-Mawardi in his Al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyyah, he famously commanded: “Do not kill women or chil dren or an old, old man, or a sick person, or a monk. Do not destroy buildings, nor cut down trees, nor harm an imals. Do not commit perfidy. Do not mutilate bodies.” T hese clear and broad prohibitions go well beyond direct combatants and include the protection of civilian lives, the preservation of agricultural land and essential food supplies, and the protection of places of worship for all religions. Additionally, they emphasize the critical prin ciples of the inviolable protection of non-combatants (hurmat al-madaniyyin) and proportionality (tanasub), which ensure that the means used are always commen surate with the legitimate military objective and do not cause excessive or indiscriminate collateral damage. T hese prophetic traditions, which have been painstak ingly recorded, verified, and passed down through rigor ous chains of narration, provide a potent and historically verifiable practical application of the Quranic teachings, clearly illustrating how moral behavior was to be upheld and given priority even in the face of the violent and chaotic realities of armed conflict.

Classical Islamic scholars began an ambitious and me thodical effort to create comprehensive legal treatises that painstakingly codified the complex laws and ethics of war, building upon these holy and foundational texts. In his seminal work Sharh al-Siyar al-Kabir (Commen tary on the Great Book of International Law by Shay bani), luminaries like Shams al-Din al-Sarakhsi (d. 1090 CE) covered every conceivable facet of interstate rela tions, including the exact requirements for lawful war fare, the humane treatment of POWs, the complete invi olability of civilian life and property, and the fair terms for peace treaties and truces. In Bidayat al-Mujtahid wa Nihayat al-Muqtasid (The Distinguished Jurist’s Primer), Ibn Rushd (Averroes) (d. 1198 CE) offered a thorough comparative analysis of various legal opinions and jur isprudential debates regarding warfare, demonstrating the depth of Islamic thought and the broad agreement regarding the moral bounds of military action. The ad ministrative, legal, and constitutional facets of conflict management were further clarified by Al-Mawardi’s (d. 1058 CE) Al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyyah (The Ordinances of Government), which firmly reaffirmed the moral behavior required of commanders and rulers as well as their ultimate duty to preserve Islamic justice and moral standards. In works like Qital Ahl al-Baghiy, even prominent scholars like Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 1328 CE), whose writings are unfortunately often misinterpreted or selectively quoted by extremist factions in modern discourse, mainly addressed internal conflicts (rebel lions or baghy). He established very strict guidelines for interaction in these situations, constantly prioritizing due process, reconciliation, and the restoration of justice over harsh or unduly violent measures. Together, these extensive and learned classical works provide a lasting testament to a deeply ingrained, extremely complex, and internally coherent tradition of ethical reasoning that was rigorously applied to the difficult and frequently tragic realities of war. This tradition frequently predates by many centuries the formal codification of much of what is now known as contemporary international humanitarian law.

DEEPENING THE FOUNDATIONAL PRINCIPLES: BEYOND JIHAD

While the initial article effectively dispels the common misconception surrounding jihad, further academic rigor necessitates a deeper exploration of other equally vital, yet often less discussed, ethical concepts that underpin Islamic jurisprudence on warfare. These concepts, rooted in both the Quran and the Sunnah, provide a robust framework for understanding the profound moral restraints and humanitarian considerations intrinsic to Islamic war ethics.

The concept of Karama, or hu man dignity, stands as a foundational pillar within Islamic ethics, transcending the specific domain of warfare to encompass all aspects of human interaction. Its roots are firmly embedded in the Quran, which declares: “And We have certainly honored the children of Adam and carried them on land and sea and provided for them of the good things and preferred them over much of what We have created, with [definite] preference” (Quran 17:70). T his verse explicitly asserts the inherent dignity bestowed upon all humanity by God, regardless of faith, race, or status.

In the context of war, the principle of Karama translates into 8 a series of strict prohibitions and obligations. It dictates that even in the throes of conflict, the inherent worth of every individual must be respected. This is why Islamic law stringently prohibits the mutilation of bodies (muthla), the torture of prisoners of war, and any acts that degrade or dehumanize an individual. The humane treatment of captives, the provision of their basic needs, and their eventual release or exchange are direct applications of Karama. As elaborated by scholars like Mohammad Hashim Kamali in Freedom, Equality, and Justice in Islam, the recognition of inherent human dignity necessitates treating even the enemy with respect, recognizing their shared humanity. T his principle further underpins the protection of non-combatants (hur mat al-madaniyyin), as their lives and well-being are deemed inviolable, not merely for strategic reasons, but due to their intrinsic human dignity. The Prophet Muhammad’s own conduct and directives, such as the prohibition against killing women, children, and the elderly, serve as concrete manifestations of this profound respect for human life and dignity even in times of intense conflict. This proactive safeguarding of vulnerable populations under scores a moral obligation that transcends mere military expediency.

Closely intertwined with Karama is the concept of Isma, which signifies inviolability or protection. This principle extends divine and legal protection to specific categories of individuals and entities, making them immune from harm during conflict. While the article briefly touches upon the protection of non-combatants, Isma provides the deeper theological and legal grounding for this crucial aspect.

The concept of Isma applies not only to individuals but also to places and property. It underscores the prohibition against the wanton destruction of civilian infrastructure, agricultural land, and places of worship, as highlighted in the Prophet’s instructions. Khaled Abou El Fadl, in his extensive works on Islamic law, often emphasizes how Isma creates a sphere of protection around those not directly engaged in hostilities, including women, children, the elderly, the sick, and religious figures. This protection is not conditional on their religion or allegiance but is an inherent right derived from their status as non-combatants. Furthermore, Isma extends to those who have been granted amān (safe conduct), making any violation of such a pledge a grave offense in Islamic law. This concept reinforces the sanctity of agreements and the imperative to honor commitments, even with adversaries. The deliberate targeting of protected individuals or entities is considered a transgression against divine law, illustrating that the permissibility of warfare is severely restricted by the overarching principle of preserving life and maintaining societal order. The emphasis on Isma clearly demonstrates that Islamic war ethics are not merely about permissible actions, but also about explicitly forbidden ones, designed to minimize suffering and uphold moral boundaries during conflict.

The legitimacy and ethical conduct of warfare in Islam are inextricably linked to the principles of Adl (justice) and Shura (consultation). These concepts dictate not only why a war may be waged but also how it must be conducted to remain within the bounds of divine and human law.

Adl, or justice, is an overarching principle in Islam that permeates all facets of life, including the decision to engage in and conduct warfare. T he Quran repeatedly emphasizes the importance of justice: “Indeed, Allah orders justice and good con duct” (Quran 16:90). In the context of jus ad bellum, Adl necessitates that war can only be waged for a just cause, primarily in self-defense or to eradicate severe oppression. It strictly prohibits aggressive, expansionist, or retaliatory warfare driven by malice or territorial ambition. As articulated by Wael B. Hallaq in A History of Islamic Legal Theories, the pursuit of justice is not merely a desired outcome but a moral imperative that must guide every step of the conflict.

Furthermore, Adl extends to jus in bello, dictating the fair and equitable treatment of all parties involved in a conflict. This includes ensuring proportionality (tanasub) in the use of force, meaning that the military response must be commensurate with the threat and should not inflict excessive or unnecessary harm. It also entails the fair distribution of resources during and after conflict, the protection of non-combat ants, and the adherence to treaties. T he concept of adl bayn al-nas (jus tice among people) underscores the idea that even in conflict, the ultimate aim is to establish a just order, not to perpetuate injustice. This means that Islamic ethics of war are not simply about stopping aggression, but about ensuring that the means employed to achieve this end . are themselves just. The prohibition against perfidy (ghadr) and the emphasis on upholding covenants (uhud) are direct manifestations of Adl, ensuring that even adversaries are treated with a degree of fairness and predictability, which is essential for any potential future peace.

The principle of Shura, or consultation, is deeply ingrained in Islamic governance and decision-making, including matters of war and peace. The Quran instructs Prophet Mu hammad: “And consult them in the matter” (Quran 3:159). While the ultimate authority rests with God, human decision-makers are encouraged to engage in extensive consultation with qualified individuals, experts, and representatives of the community before making significant decisions, especially those pertaining to declaring war.

In classical Islamic political theory, as discussed by scholars like Ann Elizabeth Mayer in Islam and the State, the decision to declare war was not to be taken unilaterally by a ruler. Instead, it required deliberation among legal scholars, military strategists, and community leaders. This consultative process ensures that the decision is well-considered, based on sound legal and ethical principles, and reflects the collective wisdom of the community. It acts as a safeguard against rash decisions, personal vendettas, or arbitrary declarations of war. The absence of Shura would render a declaration of war ethically questionable, as it would lack the communal consensus and rigorous deliberation that Islamic ethics demand. This principle contributes to the legitimacy of the authority to wage war (as part of jus ad bellum), ensuring that such a grave decision is made transparently and with broad support, thereby enhancing accountability and reducing the likelihood of unjust conflicts. In modern contexts, this principle translates into the necessity of parliamentary oversight, expert advisory councils, and public debate on matters of war and peace, reflecting the democratic spirit inherent in Shura.

UNCOVERING JIHAD: GOING BEYOND THE SWORD AND THE BATTLEFIELD

The idea of jihad is at the center of one of the most significant, enduring, and harmful misconceptions about Islamic war ethics. However, jihad in its true, complex Islamic theological and legal framework includes a holistic spectrum of struggle that goes far beyond purely military engagement. This is often, and often reductively and incorrectly, translated in popular media and political discourse as simply “holy war.” Fundamentally meaning “to strive,” “to struggle,” “to exert effort,” or “to toil,” its linguistic root, “jahada,” reflects its far more extensive spiritual, intellectual, social, and individual applications.

The concept’s historical, linguistic, and theological development has been painstakingly traced by academic titans in the fields of Islamic studies and comparative ethics, including Michael Bonner in Jihad in Islamic History: Doctrines and Practice and Reuven Fires tone in Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam. They shed light on its two main and most important differences: the lesser jihad (al-jihad al-asghar), which deals with armed conflict, specifically allowed only as defensive warfare, and the greater jihad (al-jihad al-akbar), which is the difficult, lifelong internal struggle against one’s own lower.

desires, ego, temptations, and sins in an effort to improve oneself and maintain moral purity. The greater jihad is constantly, overwhelmingly, and explicitly given priority in the Quran and the Sunnah, which see moral purification, self-improvement, and the development of virtue and piety as the most important, difficult, and spiritually fulfilling endeavors for each and every Muslim.

Importantly, military action is always framed as an extraordinary defensive necessity, an absolute measure of last resort, and always strictly subject to certain, strict moral and legal requirements when it is taken into consideration within mainstream Islamic jurisprudence. Early Islamic jurisprudence primarily saw warfare as acceptable only in direct response to aggression, to repel an attacking enemy force, or to erase severe, systemic oppression that actively prevents the free practice of faith, threatens the lives and well-being of the innocent, or obstructs the establishment of justice, as Majid Khadduri incisively explains in his seminal work War and Peace in the Law of Islam. A crucial and sadly often ignored distinction, this naturally defensive stance distinguishes legitimate Islamic warfare from unprovoked aggression, territorial expansionism, imperial conquest, or forced conversion. A major and dangerous distortion that is frequently fueled by selective readings, decontextualized verses, and extremist interpretations that are overwhelmingly rejected by the vast majority of mainstream Islamic scholars, jurists, and the global Muslim community throughout history and in the present is the widespread misconception that jihad is an offensive, expansionist doctrine intended for global domination or the forceful imposition of Islam. Such aggressive, unprovoked warfare is categorically and explicitly condemned in authentic Islamic teachings as a serious transgression of both human morality and divine law. The goal is always to preserve life, not to destroy it.

Islamic and Western Just War Theories: Similarities and Differences

In addition to the unique and distinctive contributions that Islamic ethics offer to current discussions on military conduct and international humanitarian law, a thorough and scholarly comparison of Islamic just war theory with Western philosophical and theological traditions reveals remarkable and frequently surprising convergences in their fundamental ethical concerns. Important, in-depth insights into these common and distinctively Islamic dimensions can be gained from scholarly works like John Kelsay’s Islam and War: A Study in Comparative Ethics and the painstakingly assembled collection Cross, Crescent, and Sword: The Justification and Limitation of War in Western and Islamic Tradition, edited by James Turner Johnson and John Kelsay.

Fundamental ideas that guide the start of war (jus ad bellum) and the conduct of war (jus in bello) are shared by the Islamic and Western just war traditions. The fundamental requirements of jus ad bellum are as follows: a just cause (usually understood to be legitimate self-defense, resistance to obvious aggression, or the end of extreme, pervasive oppression and tyranny); legitimate authority to declare and wage war (such as a recognized state, a legitimate sovereign, or an established legal authority, not rogue individuals or groups); and the underlying right intention, which states that the ultimate and sincere goal of the conflict must always be to achieve a just and lasting peace, to restore order, or to eradicate oppression, not just for personal vengeance, territorial conquest, or financial gain. Both frameworks also place a strong emphasis on discrimination (also known as non-combatant immunity or the principle of distinction), which is the unwavering and absolute need to distinguish clearly between combatants and non-combatants in order to protect civilians from direct and intentional attack and to protect their lives and property to the greatest extent possible. Proportionality (tanasub) is the idea that the expected harm caused by military action must always be proportionate and must not outweigh the legitimate military or political good sought to be achieved. Many of these universal ethical concerns are echoed in Michael Walzer’s Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations, a seminal and highly influential work in Western just war theory. It effectively highlights a human impulse shared by people from diverse cultures and civilizations to control, limit, and lessen the inherent savagery and destructive potential of war.

But Islamic ethics add unique subtleties and deep emphasis that greatly enhance the larger international conversation on war. The core focus on tawhid the ultimate sovereignty of the Divine and the absolute oneness of God gives Islamic ethical philosophy a strong, comprehensive sense of ultimate accountability to a higher moral and spiritual authority. Accordingly, moral issues in combat are not just political expediencies, utilitarian considerations, or pragmatic calculations; rather, they are mandated by God and are considered sacred duties. A stronger, more steadfast, and more deeply rooted dedication to moral limits and ethical restraints even when such adherence might seem strategically counterproductive in a purely pragmatic sense is frequently the result of this deep spiritual dimension. Beyond short-term tactical advantages, the sanctity of human life and the pursuit of justice are regarded as divine mandates.

Moreover, amān, which means “safe conduct, protection, or pledge of security,” is a very strong and legally binding concept in Islam. It requires rigorous and unbreakable adherence to assurances of safety given to people, including non-combatant civilians or enemy combatants who seek protection, even if they are made by a single Muslim without express orders from a higher authority. This emphasizes the moral agency and duty of the individual to maintain justice. A highly developed and principled framework for diplomatic engagement, the cessation of hostilities, and long-term conflict resolution is highlighted by the strong emphasis on upholding treaties and covenants (uhud) with absolute fidelity, even with adversaries or non-Muslim states, and the grave prohibition against perfidy, treachery (ghadr), or breaking promises. This framework significantly predates and frequently surpasses many contemporary international law frameworks in its explicit moral demands. A deeply rooted and compassionate humanitarian impulse that extends even to those deemed adversaries is further exemplified by Islamic tradition’s explicit prohibition against the mutilation of bodies (muthla), the respectful treatment of the dead, and the humane and dignified treatment of prisoners of war. Together, these all-encompassing values represent a deep and universal moral code that aims to protect and maintain human dignity despite the extreme violence and mayhem of war.

Current Uses: Handling the Difficulties of Contemporary Combat

The traditional tenets of Islamic war ethics are not merely artifacts from antiquity; rather, they provide a strong, adaptable, and highly significant foundation for dealing with the unparalleled complexity and quickly changing character of contemporary warfare. Current implementations of these timeless principles are being actively investigated, discussed, and used in a variety of settings, from conventional interstate military conflicts and intricate counter-insurgency operations to the new and morally difficult fields of cyberwarfare, drone technology, artificial intelligence in combat, and asymmetric conflicts involving non-state actors.

For example, in the era of precision-guided weapons, drone attacks, and the growing dependence on remote warfare, the principle of proportionality (tanasub) assumes crucial new dimensions and increased significance. Although these technologies are frequently praised for their capacity to reduce civilian casualties, the possibility of unintentional collateral damage to non-combatants is still a serious worry that necessitates ongoing ethical consideration. The ways in which these contemporary military strategies and technologies conform to the stringent prohibitions against injuring non-combatants and causing needless or excessive destruction are the subject of intense jurisprudential discussions among Islamic legal scholars and ethicists. They carefully investigate whether remote warfare technologies, like armed drones, actually adhere to the principle of discrimination in situations where the operator is physically separated from the battlefield, intelligence collection may be subpar, and the possibility of misidentification or civilian casualties while statistically lower remains a persistent ethical dilemma. Similarly, the ethics of cyberwarfare, which fundamentally blurs the traditional lines between combatants and civilians, military infrastructure and critical civilian services (such as power grids, financial networks, and healthcare systems), and which can have a widespread, debilitating impact on society, are being carefully examined through the fundamental lens of Islamic principles of non-transgression, the absolute protection of innocent life, and the preservation of societal well-being (maslaha). The Islamic Law of War: Justifications and Regulations by Ahmed Al-Dawoody offers a thorough and sophisticated examination of these urgent contemporary issues within the context of modern Islamic law, effectively showcasing the exceptional flexibility and ongoing applicability of traditional Islamic jurisprudence.

Furthermore, these deep ethical principles are being actively and consciously incorporated into the modern military doctrines, professional training protocols, and involvement in international peacekeeping operations of an increasing number of Muslim-majority countries and their highly developed military institutions. This intentional and thoughtful integration shows how to balance deeply held religious ethical commitments with the operational and professional responsibilities of contemporary military forces in pluralistic national and international societies in a way that is realistic, efficient, and morally sound. It provides a potent refutation of the radical distortions of Islamic doctrine.

The urgent and essential need to confront and actively combat the widespread misunderstandings and the heinous, violent appropriation of core Islamic ideas especially the distortion of jihad by extremist groups is perhaps one of the most important and urgent aspects of studying Islamic ethics of war in the modern world. In order to rationalize their ruthless sectarianism, indiscriminate violence, and savage acts against both Muslim and non-Muslim populations, organizations such as ISIS (Daesh), Al-Qaeda, Boko Haram, and other violent non-state actors cynically, purposefully, and maliciously misrepresent sacred Islamic texts and principles. The great majority of respectable Islamic scholarship, religious organizations, and the Muslim community worldwide have categorically, universally, and vehemently rejected such extremist interpretations and actions throughout history and in the present. They represent a radical, violent, and illegitimate departure from the mainstream, historically consistent, and ethically rigorous interpretations of Islamic law and morality.

The comprehensive and objective examination of Islamic war ethics clearly shows that, rather than advocating unbridled violence, unbridled aggression, or coerced conversion, these ethics actually place far more stringent and incredibly humane restrictions on warfare than many secular international law frameworks had until recently. The specific prohibitions against willfully targeting civilians, willfully destroying property and essential infrastructure, and engaging in perfidy, treachery, or breaking solemn covenants all make this remarkable adherence to moral boundaries very clear. A strong, enduring, and divinely mandated commitment to moral behavior based on divine commandments and the model prophetic example is underscored by the strong and constant emphasis on actively seeking peace, even with adversaries, and the strong legal framework for the humanitarian and dignified treatment of all individuals in conflict zones including enemy combatants, prisoners of war, the wounded, and especially non-combatants. These values are essential to the foundation of Islamic justice and cannot be disregarded.

The Ethics of Cyberwarfare and AI in Combat

The enduring relevance of Islamic ethics of war is particularly evident in their application to contemporary challenges, pushing scholars and policymakers to bridge traditional jurisprudence with the complexities of modern conflict.

The rapid advancement of technology introduces new ethical dilemmas that necessitate a flexible and robust interpretive framework. Cyberwarfare and the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in combat are two such areas where Islamic ethics provide crucial guidance.

In cyberwarfare, the principle of discrimination (non-combatant immunity) becomes particularly challenging. Attacks on critical civilian infrastructure, such as power grids, healthcare systems, or financial networks, while not involving kinetic force, can have devastating consequences for civilian populations, violating Isma. Islamic jurists applying the principle of maslaha (public welfare) would likely condemn such indiscriminate cyberattacks, as they cause widespread harm and disruption to innocent lives, far outweighing any legitimate military objective. The potential for unintended collateral damage in the digital realm necessitates careful consideration of proportionality (tanasub).

Similarly, the deployment of autonomous weapon systems (lethal autonomous weapons systems - LAWS) powered by AI raises profound ethical questions regarding human accountability and the sanctity of human life. The principles of Karama (human dignity) and Isma (inviolability) would necessitate a robust human oversight to prevent machines from violating the inherent worth and protection due to individuals. Furthermore, the capacity for AI to learn and potentially act outside predefined ethical parameters could lead to disproportionate harm or the targeting of non-combatants, directly conflicting with Islamic ethical injunctions. Scholars are actively engaging with these emerging technologies, seeking to apply traditional principles to novel scenarios, emphasizing human control and accountability in all military operations to uphold the sanctity of life and avoid transgression.

The Environment in Islamic War Ethics

An often-overlooked aspect of Islamic war ethics is its profound concern for the environment and natural resources. The prophetic injunctions to “not cut down trees, nor harm animals” (as mentioned in the original text) are not merely humanitarian but also ecological. This reflects a broader Islamic worldview that views humanity as khalifa (stewards) of the Earth. Deliberate destruction of agriculture, water sources, or the environment for military advantage is considered a grave transgression. This principle of environmental protection in warfare aligns with contemporary concerns about ecocide and the long-term impact of conflict on ecosystems. This prohibition ensures the sustainability of life and resources for future generations, preventing the despoliation of land and livelihood, which would undermine the very fabric of society that legitimate warfare aims to protect or restore.

Fostering Cross-Cultural Dialogue and Global Peace

The detailed exploration of Islamic ethics of war serves a purpose beyond academic understanding; it is a vital step in fostering cross-cultural dialogue and contributing to global peace. By highlighting the sophisticated ethical framework within Islam, it counters simplistic and often hostile narratives that contribute to Islamophobia and misunderstanding.

The emphasis on peace (salam) as the ultimate objective of all legitimate actions, including defensive warfare, is a recurring theme in Islamic teachings. The Quranic verse “And if they incline to peace, then incline to it also and rely upon Allah” (Quran 8:61) is not merely a permissive statement but an active encouragement to pursue diplomatic solutions and cease hostilities at the earliest opportunity. This proactive pursuit of peace, even with adversaries, demonstrates a fundamental preference for non-violent resolutions. The intricate rules governing truces, treaties, and safe conduct in Islamic law further underscore this commitment to building stable and peaceful relations.

The convergence of Islamic and Western just war traditions on core principles like just cause, legitimate authority, discrimination, and proportionality offers a powerful foundation for universal humanitarian principles. This shared ethical ground can serve as a basis for enhanced cooperation in international law, humanitarian aid, and conflict resolution efforts. Recognizing these commonalities can help to bridge divides and foster mutual respect among diverse civilizations and legal systems.

Ultimately, the Islamic moral code for war stands as a testament to the enduring human quest for moral order, even in the most chaotic of circumstances. By delving into concepts like Karama, Isma, Adl, and Shura, alongside a nuanced understanding of jihad, we gain a richer, more accurate picture of a tradition that prioritizes human dignity, justice, and peace. This deeper understanding is not only crucial for dispelling myths but also for leveraging these profound ethical insights in our collective pursuit of a more just, humane, and peaceful world. The rigorous scholarship within Islamic jurisprudence provides a timeless framework that continues to offer profound guidance for navigating the complexities of armed conflict and aspiring towards a future where peace truly prevails.

Conclusion

The comprehensive exploration of Islamic ethics of war reveals a profound, intricate, and remarkably consistent framework guiding armed conflict for over fourteen centuries. Far from endorsing unbridled aggression, this ethical system, rooted in the Quran and the Sunnah, rigorously prioritizes moral restraint, proportionality, and humanitarian considerations. Core principles like Karama (human dignity), Isma (inviolability), Adl (justice), and Shura (consultation) are foundational tenets, permeating every aspect of permissible warfare. These enduring values underscore a deep commitment to human life and societal well-being. This framework stands in stark contrast to extremist ideologies, which misrepresent these teachings for violent agendas, causing widespread suffering and misperceptions. It is a testament to a rich tradition seeking peace amidst armed engagement.

The pervasive misconception of “jihad” as solely “holy war” has been a significant barrier. This article clarifies that jihad encompasses a broader struggle, with defensive armed conflict being a last resort, strictly limited by ethical parameters. This understanding is crucial for dispelling dangerous distortions propagated by extremist groups, whose actions are universally condemned by mainstream Islamic thought. Such clarifications are vital for promoting accurate understanding and countering narratives that fuel conflict. Educating the public on these nuanced interpretations is paramount for global harmony.

The enduring relevance of Islamic war ethics is evident in their application to contemporary challenges like cyberwarfare and AI in combat. These principles provide a robust ethical compass, emphasizing accountability, human oversight, and minimizing harm to civilians. Islamic emphasis on environmental protection further highlights this system’s holistic nature. By fostering cross-cultural dialogue, we can collectively work towards universal humanitarian principles. Islamic ethics of war offer invaluable guidance for navigating conflict and striving for a more just, humane, and peaceful world. Their timeless wisdom offers a path towards resolving modern warfare's complexities with compassion and justice. Its universal applicability extends beyond religious boundaries.