The Fractured Ummah: Crisis in the Muslim World

The contemporary Muslim world grapples with profound fragmentation, a stark contrast to its historical unity. This dismemberment into nation-states, sectarian divisions, and proxy conflicts is largely attributable to artificial borders drawn by colonial powers. This analysis delves into factors weakening the Umma's principles

The Umma, representing , the global Muslim community, has historically been a powerful unifying force, transcending geographical, cultural, ethnic, and linguistic boundaries. This community was bound by shared faith and religious obligations, and its solidarity extended beyond political disagreements. Beyond the rational and legal sources explained in order to understand the sources of this strong solidarity, there is come conventional interventions, as depicted by Ibn Tymiyya, and the Quran explicitly referred to Muslims as one Umma, emphasizing unity as a fundamental principle alongside Tawhid, substantiating the role of the Umma as an Islamic community founded by Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and united by religious ties across diverse geographical and cultural manifestations throughout history.

However, the Muslim world today faces an unprecedented crisis of fragmentation, living within artificial borders drawn by colonial powers. The once-unified Umma, despite its diverse cultural and ethnic relations, has been fragmented into competing nation-states, sectarian divisions, and proxy conflicts. Propaganda, sectarianism, and the prioritization of narrow national interests have eroded the collective strength of the Arab and Muslim world. This fragmentation is evident in the inability of nations to respond effectively to crisis faced by co-religionists, and the subjugation of political and religious authority to external forces undermining the foundational principles of Islamic solidarity and cooperation.

The initial understanding of the fragmented Umma draws from Benedict Anderson's work on "imagined communities," which suggests that nationalism filled the void left by the decline of grand religious communities like Latin Christendom and the Muslim Umma. Anthony Smith's ethno-symbolic approach and the division between civic and ethnic nationalism further illuminate the transition of Muslim communities from traditional religious identities to modern nation-states. Partha Chatterjee's critique of derivative nationalism explains why Western models of nation-building have been problematic in the Muslim context. This analysis aims to examine the historical aspects of this fragmentation, in both ideological and material realms, in order to understand the root causes of fracture that debilitated the principles of Umma. The analysis will explore the nature of instability through three primary lenses: historical analysis of fragmentation, contemporary sources of division, and case studies such as Palestine and Kashmir. The primary focus will be on the history of instability, incorporating both Western and Islamic viewpoints providing comprehensive understanding of contemporary Muslim political fragmentation and disunity.

The concept of Umma began with the establishment of the first Islamic state in Medina under the Constitution of Medina in 622 CE. This demonstrates the socio-political conditions that Ibn Khaldun defined as "Asabiyya" in the second stage of community formation. This implies that religion was primarily formed, and subsequently, a state was established to mark the rise of a new civilization. While the term "Islamic state" is used in modern scholarship, the constitution and authority were merely an external material form of the Umma. This material form evolved into a more structuralist entity, acclaimed by the unity within the Umma, which facilitated Islam's development into a civilization, marking its golden age between the 8th and 13th centuries, characterized by remarkable intellectual, scientific, and internal cultural flourishing. Fernand Braudel noted that at the peak of Islamic power, only Chinese civilization was comparable in level, quality, and variety of achievement, but it remained localized. In contrast, Islam created a polyethnic, multiracial, international, and intercontinental world civilization, and the Umma remained unified amidst its diversities establishing foundations for subsequent Islamic political and cultural developments.

Arabic became the international language, and Muslim states were powerful, simultaneously invading Europe, Africa, India, and China. They were also economic powers with key trade advantages and production mediums. The unified Umma helped Muslims achieve a civilization's zenith. This development aligns with Ibn Khaldun's view of escalation in science and technology as a civilization's peak, followed by deterioration. However, it is contradictory that there has been no revival of actual unity in this regard despite numerous attempts at pan-Islamic movements and political unification.

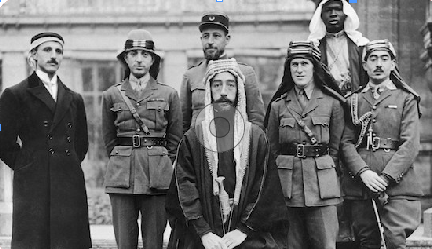

In the modern political dynamics, for centuries, the Ulama maintained Muslim consciousness under the Ummah. Despite disparities and fragmentations among Muslim ruling parties, these differences were often overridden by a collective consciousness of being part of the Ummah. This unity ended with the decline of the Ottoman Empire, the last major Islamic Caliphate. The Ottoman decline is often traced to the death of Sulayman the Magnificent and the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 CE, where Christian civilizations defeated Ottoman naval forces. The 19th century saw accelerated decline with military defeats and territorial losses. The Tanzimat reforms (1839-1876 CE) were desperate attempts to modernize the empire through selective Westernization. The empire, which survived according to the hypothesis of a Russian Muslim sociologist, finally ended with its abolition by Mustafa Kamal Ataturk in 1924. Beyond the rejection of the Caliphate, a critical loss was the common space for global Muslim unity marking the definitive end of traditional Islamic political authority.

This period marks a turning point where Ulama failed to respond to excessive colonial intervention in Islam and Islamic states. Crucial elements of Islamic history were manipulated by Western colonial structures to form a new global order, leading to drastic disaster in the Islamic world. Western colonial intervention exacerbated all sources of instability, highlighting the incapability of learning from colonialism and establishing patterns of dependency that persist in contemporary politics.

European colonizers profoundly transformed the Muslim world by imposing new political structures that contradicted Islamic concepts of governance and community organization. From the 18th century onwards, European colonial powers impacted Muslim-majority societies in Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. The colonial period, though less than two centuries, altered all aspects of geography, economy, social relations, and politics in these regions. For example, colonial powers systematically dismantled traditional Islamic institutions, particularly the Waqf system. Historians note that dismantling the Waqf system was essential for colonial missions, both to acquire resources and to subjugate local populations fundamentally reshaping Islamic social and economic structures across multiple regions.

Some argue that about half of all Muslim land was tied to a waqf (Islamic endowment) when Europeans exerted control. The imposition of nation-state systems fundamentally contradicted Islamic political theory. The Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916 was a foundational moment in the fragmentation of the Muslim world, effectively dividing Ottoman provinces outside the Arabian peninsula into areas of British and French control, creating artificial borders that ignored existing ethnic, tribal, and religious boundaries. Scholars reveal that the agreement's impact extended beyond mere territorial division, and its secretive nature and imperial motivations shaped a political order characterized by artificial borders, fragmented societies, and contested sovereignties. This agreement exemplified what critics call the colonial mindset of externally imposed statehood, creating inherently unstable states lacking broad legitimacy with consequences that continue to shape Middle Eastern politics today.

This agreement ultimately led to the further fragmentation of the Islamic world into nation-states. Modern nation-state notions fundamentally contradict Islamic religious and legal principles. Wael Hallaq persuasively argues that the modern state, as a construct rooted in European Enlightenment ideals, is fundamentally incompatible with Islamic modes of governance. His critique rests on the observation that the modern state is inherently centralized, bureaucratic, and predicated upon sovereignty and the monopoly of violence characteristics that conflict with the decentralized, moral, and jurisprudential nature of traditional Islamic governance. In this light, the modern state not only imposes a structure alien to Islamic political theory but also subordinates Sharia to positive law, thereby compromising its normative authority. Classical Muslim thinkers like Al-Mawardi similarly emphasized that the unity of the Ummah (global Muslim community) hinges on a network of reciprocal obligations between ruler and ruled, grounded in Islamic legal and ethical principles. For Al-Mawardi, legitimate political authority is conditional upon the ruler's adherence to divine law and his duty to uphold justice and public welfare, a vision that starkly contrasts with modern forms of secular nationalism.

Imam Abu Hamid al-Ghazali further advanced a theo-democratic model in which political authority derives its legitimacy not merely from power or procedural mechanisms, but from its conformity to the moral and spiritual goals of Islam. His framework centers on the idea of maslaha (public interest) and insists that political leadership must safeguard both material and spiritual well-being. In the contemporary landscape of postcolonial Muslim nation-states, which often operate under secular constitutions, such classical formulations appear increasingly marginalized despite their continued relevance.

Nevertheless, Ibn Taymiyya's concept of Siyasa Sharʿiyya (governance according to Sharia) offers a potent rejoinder to secular paradigms. He contended that rulers must be guided by Islamic legal principles to ensure legitimacy and justice. This perspective rejects secular nationalism as a basis for authority, asserting instead that political legitimacy must be anchored in divine revelation and the moral imperatives of Sharia. These divisions into multiple nation-states allowed colonial agents to fuel turmoil in the Middle East.

Throughout Islamic history, ideological differences have ranged from political theories on the Caliphate to epistemological disunity and the Sunni-Shia division, which originated from claims for the Caliphate and has been deeply politicized. State and non-state actors exploit these divides for local rivalries, as seen in Bahrain, Syria, and Iraq. Intellectual rifts also exist among Muslim schools of thought perpetuating divisions that weaken overall Islamic political and social cohesion.

The historical tensions within Islamic intellectual and theological traditions such as those between thinkers like Al-Ghazali and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) were once vibrant engines of epistemological growth and philosophical refinement. Al-Ghazali, in his famous Tahafut al-Falasifa (The Incoherence of the Philosophers), critiqued Ibn Sina's application of Aristotelian-Neoplatonic philosophy to Islamic metaphysics, particularly challenging notions such as the eternity of the world and the denial of bodily resurrection. Rather than stifling knowledge, such engagements catalyzed rich debates that encouraged subsequent scholars, notably Ibn Rushd (Averroes), to respond in defense of philosophical inquiry. In Tahafut al-Tahafut (The Incoherence of the Incoherence), Ibn Rushd sought to reconcile reason and revelation, arguing that philosophy and religion are not mutually exclusive but complementary. These intellectual exchanges, despite their tensions, contributed to a pluralistic and dynamic tradition of Islamic thought, where reason ('aql) and revelation (naql) were debated, negotiated, and integrated in sophisticated ways fostering intellectual diversity.

The theological discourse between the Ash'ari and Maturidi schools similarly reflects the diversity of Islamic thought. While both schools are rooted in Sunni orthodoxy and seek to defend Islamic creed against theological deviation, they differ in subtle but significant ways. Ash'arism, founded by Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari, emphasized occasionalism and divine omnipotence, at times subordinating reason to revelation. In contrast, the Maturidi school, associated with Abu Mansur al-Maturidi, placed a stronger emphasis on human reason in discerning moral truths and understanding divine justice. These theological nuances were not divisive in a destructive sense; instead, they allowed for regional diversity, such as the prevalence of Maturidism in Central Asia and the Ottoman world, and Ash'arism in the Arab heartlands and North Africa.

Jurisprudentially, the coexistence of the four Sunni madhhabs Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, and Hanbali further illustrates Islam's historically inclusive approach to legal pluralism. Scholars engaged in ikhtilaf (juristic disagreement) with mutual respect and acknowledged the legitimacy of variant rulings within the bounds of Sharia. The diversity of opinions was managed within a shared framework of usul al-fiqh (principles of jurisprudence), ensuring both legal flexibility and coherence. This capacity to accommodate difference was a hallmark of pre-modern Islamic civilization providing models for contemporary Islamic legal and political pluralism.

However, in the contemporary era, such intellectual diversity has devolved into rigid ideological partisanship and sectarian fragmentation. Instead of contributing to knowledge, debates are increasingly politicized, manipulated by state interests, and influenced by external geopolitical agendas. For instance, the introduction of Qadianism during British colonial rule in India promoting quietist and pro-establishment interpretations of Islam was a deliberate attempt to weaken pan-Islamic solidarity and dilute resistance movements. This colonial legacy persists in various forms today, where external actors and so-called "Western hatred factories" continue to exploit religious differences to divide Muslim communities undermining the productive intellectual traditions that once strengthened Islamic civilization.

Moreover, contemporary political fault lines exacerbate these divides. Turkey and Qatar have emerged as patrons of political Islam, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood, promoting Islamic governance models with populist undertones. In contrast, Saudi Arabia and the UAE adopt an anti-Islamist stance, often branding the Brotherhood as a terrorist organization. These geopolitical rivalries play out violently in countries like Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and Syria, where ideological affiliations have become entangled with state-building, rebellion, and repression. As a result, the once-productive tensions of the Islamic intellectual tradition are being repurposed as tools for political division, eroding the universal spirit of Islamic knowledge and fostering instability across the Muslim world transforming scholarly discourse into instruments of political manipulation and regional conflict.

The fragmentation of the Muslim world in the contemporary era cannot be fully understood without examining the persistent role of proxy wars, many of which are rooted in historical patterns of colonial interference and perpetuated by modern geopolitical interests. These proxy conflicts, largely fueled by the strategic ambitions of external powers such as Britain and the United States, have turned various Muslim-majority regions into enduring zones of instability and sectarian conflict. The implications of these interventions are far-reaching, shaping not only the domestic politics of Muslim nations but also the collective identity and unity of the Muslim Ummah creating cycles of violence that serve external interests over Muslim welfare.

Proxy wars are a form of indirect warfare where external powers support opposing factions within a third-party state, often to advance their geopolitical objectives without bearing the costs of direct military engagement. In the Muslim world, such wars have proliferated due to a combination of internal vulnerabilities such as weak state institutions, sectarian divisions, and economic dependency and external meddling by global powers seeking to exploit these fissures. The Cold War era intensified these dynamics, as the US and the Soviet Union vied for influence in the Middle East and beyond, turning countries like Afghanistan into violent theatres of ideological confrontation. These patterns did not end with the Cold War but evolved into newer forms of conflict, often wrapped in the language of counterterrorism, democratization, or regional security perpetuating instability that prevents authentic Islamic political development and unity.

The Saudi-Iranian rivalry is perhaps the most illustrative example of how proxy wars have fractured the Muslim world. Though rooted in theological differences between Sunni and Shia Islam, the contemporary conflict is largely geopolitical, with both states vying for regional hegemony. Yemen has become a tragic example of this rivalry, where the Houthi rebels, allegedly backed by Iran, have been battling a Saudi-led coalition for nearly a decade. The result has been catastrophic: a collapsed state, a humanitarian crisis, and the destruction of any semblance of national unity. Similar dynamics can be observed in Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, where sectarian allegiances are frequently weaponized by external actors to advance their strategic agendas demonstrating how geopolitical rivalries exploit religious identities for strategic purposes.

Palestine and Kashmir represent two of the most egregious cases of externally manufactured conflicts with deep colonial roots. The British Empire played a central role in both, laying the foundations for protracted unrest that continues to this day. In Palestine, Britain's 1917 Balfour Declaration promised a homeland for the Jews in a land already inhabited by Palestinians, without their consent. The subsequent British Mandate facilitated Zionist migration, land acquisition, and paramilitary organization, while undermining indigenous Palestinian political structures. When Britain hastily withdrew in 1948, the stage was set for the Nakba (catastrophe), in which over 700,000 Palestinians were displaced. The creation of the state of Israel was not just the result of Jewish aspirations but also a calculated imperial maneuver to maintain Western influence in the Middle East through a proxy settler state. Since then, Palestine has been a flashpoint of global tensions, manipulated by foreign powers who rhetorically support peace while materially enabling occupation and apartheid illustrating the enduring impact of British imperial duplicity and strategic manipulation.

Kashmir's story is equally emblematic of British imperial legacy. Upon the partition of India in 1947, Britain left behind a poorly defined and volatile geopolitical arrangement. The princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, with a Muslim-majority population but a Hindu ruler, became the site of conflicting claims between India and Pakistan. British policies had already sowed communal distrust through decades of divide-and-rule tactics, and their ambiguous handling of Kashmir's status created a perpetual source of conflict. The region has since seen multiple wars, decades of military occupation, and a population subjected to systemic human rights abuses. Just like Palestine, Kashmir has been internationalized, with global powers periodically weighing in nott to resolve the conflict, but often to use it as leverage in broader strategic calculations exemplifying how colonial legacies continue to generate conflicts serving external interests.

In all these cases, external interventions have not only exacerbated existing tensions but also hindered the emergence of autonomous, unified political orders within the Muslim world. Proxy wars thrive where sovereignty is weak and identity is fragmented, and the Muslim world has been systematically subjected to both conditions by external designs. The consequences are profound: a disunited Ummah, perpetual cycles of violence, and the subordination of Islamic political agency to the interests of global powers. To reverse this fragmentation, Muslim societies must reckon with these historical truths, rebuild cross-national solidarities, and reject externally imposed frameworks of division while developing indigenous solutions rooted in Islamic principles and values.

In conclusion, the enduring instability across much of the Muslim world and indeed, many of the world's contemporary ideological and territorial conflicts can be traced back to the deliberate and systematic interference of the British Empire. Far from being a neutral arbiter of peace or civilization, Britain played a decisive role in redrawing borders, inflaming sectarian and ethnic divisions, and establishing illegitimate political structures that served its colonial interests. Whether it was through the imposition of arbitrary state boundaries in the Middle East, the betrayal of the Palestinian people through the Balfour Declaration, or the deliberate fragmentation of the Indian subcontinent resulting in the Kashmir dispute, Britain acted with calculated hypocrisy preaching liberal values and self-determination while simultaneously undermining indigenous sovereignty and unity creating lasting patterns of instability that continue to plague global politics.

The legacy of this duplicity continues to shape the modern world. British colonial administrators institutionalized sectarianism, empowered compliant elites, and engineered proxy frameworks that would ensure long-term instability and dependency. In many cases, these imperial strategies were not merely accidental outcomes but deliberate mechanisms to prevent the emergence of a strong, unified Muslim political entity. Today's crises in Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Palestine, and Kashmir are not isolated or spontaneous; they are symptoms of a historical pathology rooted in Britain's imperial ambitions. Moreover, the ideological conflicts now framed as theological or civilizational clashes are often the outgrowths of colonial epistemologies and power structures imposed from above requiring honest acknowledgment of historical responsibility for contemporary global conflicts.

To speak of peace and stability in the Muslim world without acknowledging Britain's foundational role in creating these crises is to ignore the historical record. The hypocrisy of Britain lies not only in its past crimes but in its ongoing refusal to reckon with them. Until these truths are openly addressed and confronted, genuine justice and unity within the Muslim world and beyond will remain elusive demanding comprehensive historical reckoning and transformative approaches to international relations.